Early 2025, ACMI, the Australian museum of screen culture, put out a call for comissions for Game Worlds. They wanted to commission microgames from Australian developers, and the brief was deliberately open: make something playable for a museum context, 5-10 minutes of experience, ready in two months. The games were to feature compelling world-building, interesting relationships between player and maker, be easily understood by a wide variety of visitors in terms of game design, playability and mechanics, and be a playful, and thoughtful response to the context of ACMI as a museum of screen culture.

We were excited to pitch, but after brainstorming a few ideas, we realised that we wanted to do something that was a bit different. Something that would be a bit of a surprise.

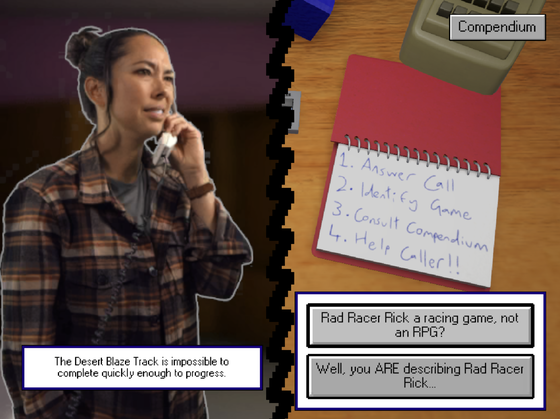

So we pitched a ridiculous idea Paris had: a hint line simulator with a 300-page physical binder.

Nobody remembers the people

You knew hint lines existed, right? 1-900 numbers, long-distance charges, hoping whoever answers actually knows what they’re talking about. They had incomplete documentation, contradictory notes, whatever the previous shift scribbled down. Nintendo’s Power Line is probably the most famous example. There’s a few great videos floating around about them.

But who were those people? People rarely talk about them, and the mechanics and infrastructure of their work is largely forgotten.

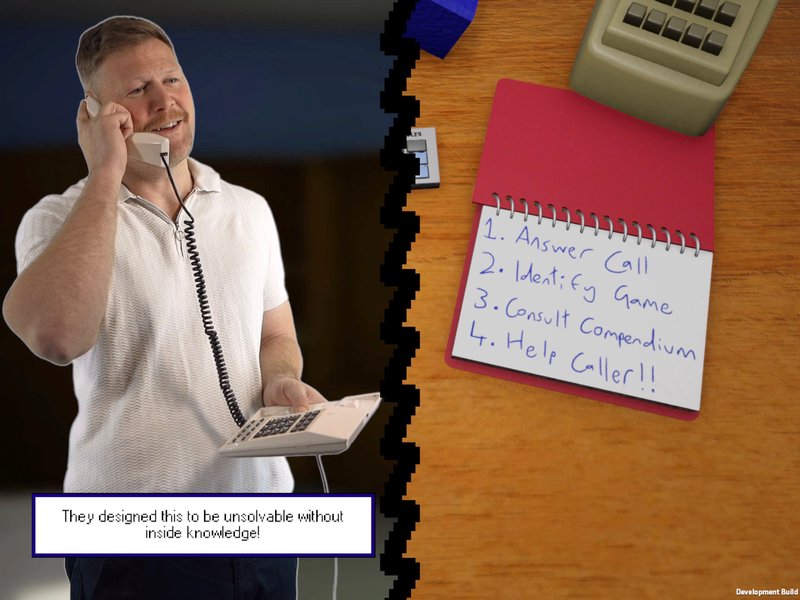

Our pitch wasn’t “hey remember hint lines?” It was “you’re going to work at one.” The solution to problems wouldn’t be on screen. They’d be in a real physical binder on the desk next to you. Like Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes, where you need information that lives outside the game.

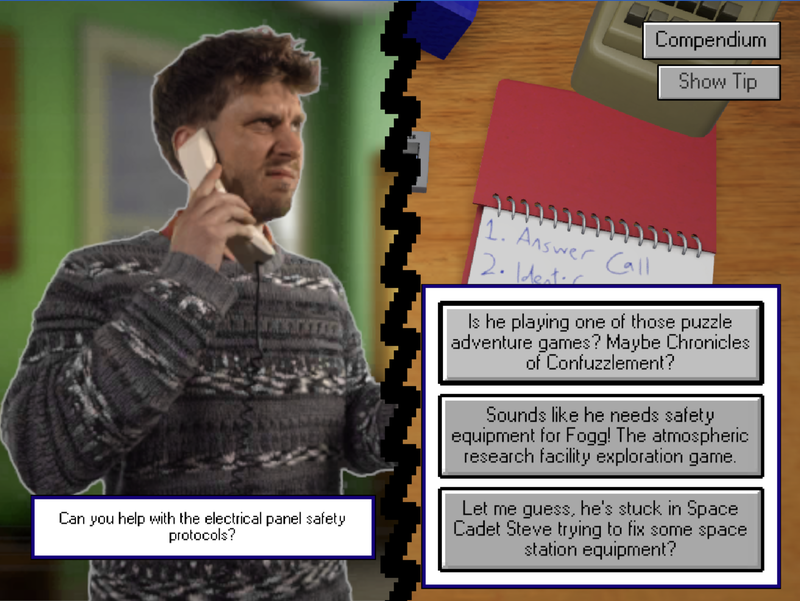

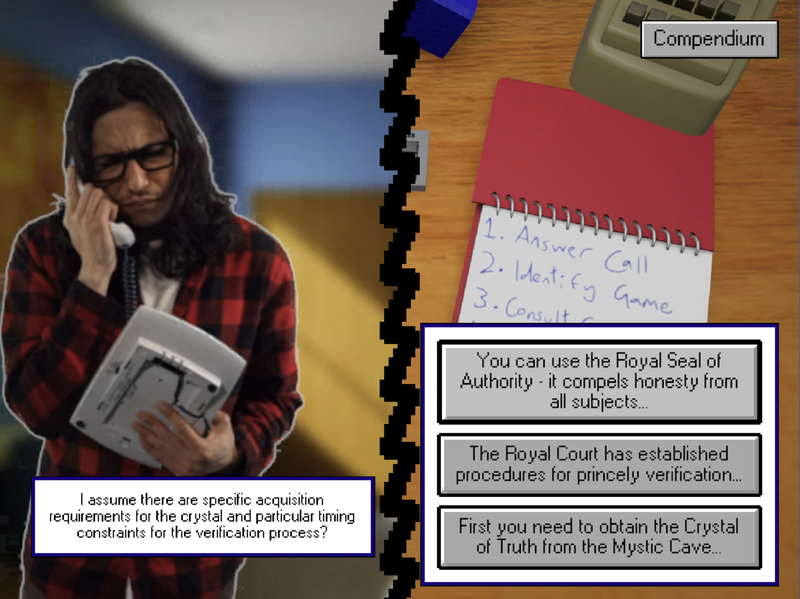

Hint Line ‘93 would be a visual novel on screen, where you’re working a fictional hint line, with critical information in The Compendium, a dog-eared binder full of official docs mixed with handwritten notes from previous counselors who figured out what actually works.

ACMI’s response was basically “this sounds completely impractical and we love it.”

Making up Damocles Interactive

The commission meant we had two months to build a complete universe. Not just a game, but a fictional company with history, games with their own design logic, documentation that feels like it accumulated over years instead of being designed yesterday.

Our fictional company, Damocles Interactive needed a corporate history, so naturally they got acquired six times by increasingly absurd companies. A beef processing consortium, a crystal healing supply business, a professional wrestling promotion, a precision calculator manufacturer, and more. Each acquisition left marks on the company culture and more importantly, on the documentation quality.

The fictional console itself, the Damocles SWORD, is a bit of a mess. It’s got a cartridge, of course, an overly complex controller, and is deeply, deeply over-engineered. It was a premium product.

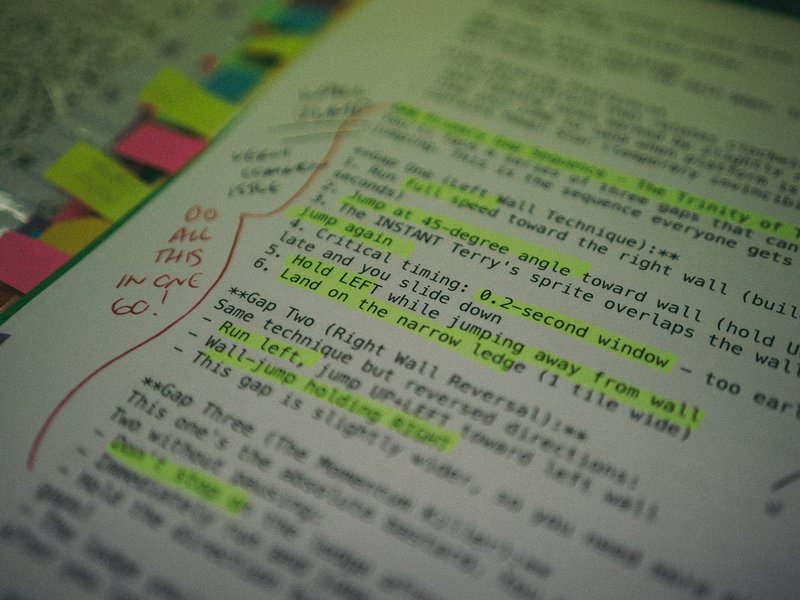

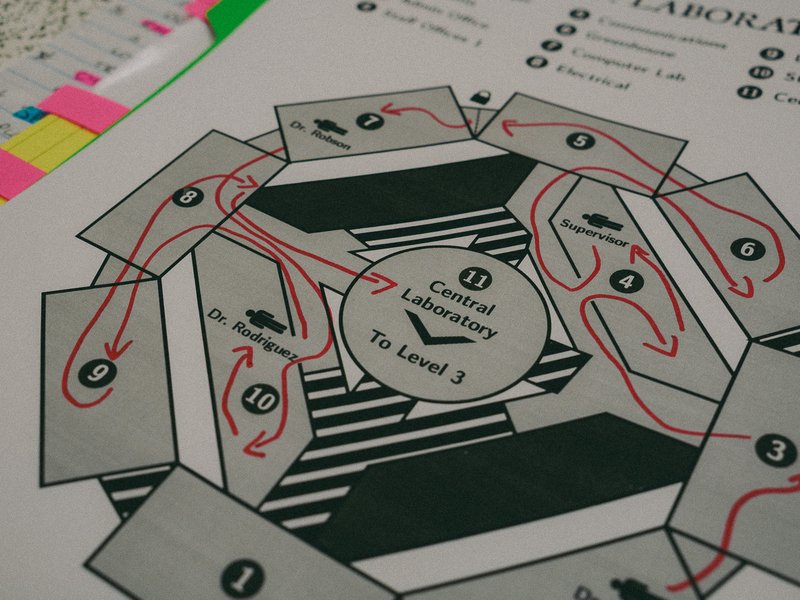

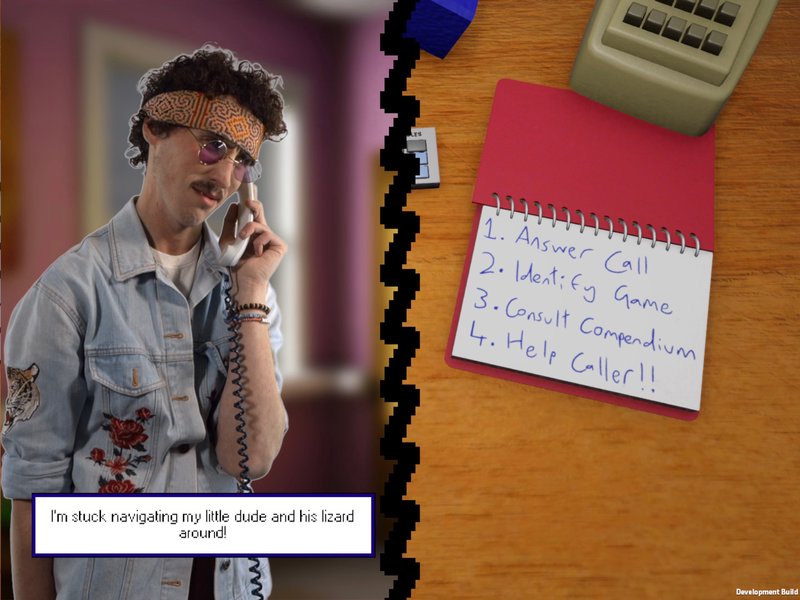

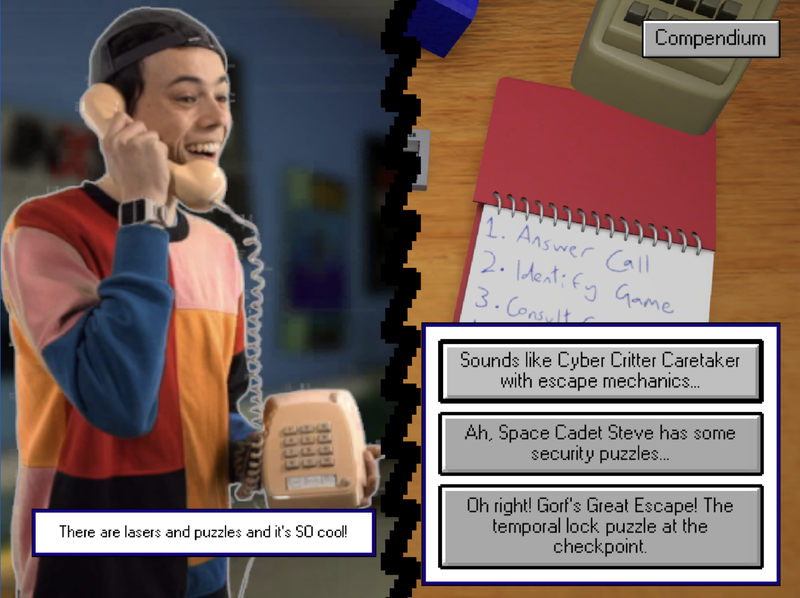

The games themselves had to feel authentically obtuse without being actually unfair. Gorf’s Great Escape, for example, is a sci-fi platformer where you navigate a space prison. You control Gorf, an alien protagonist who needs to escape through increasingly convoluted levels. The manual claims certain shortcuts exist. The hint line operators know half of them are lies.

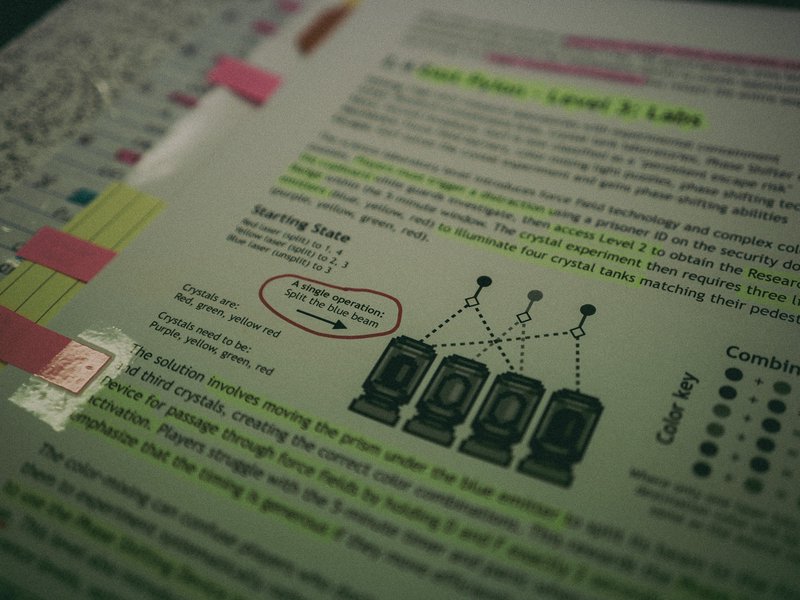

One puzzle requires standing perfectly still under a flickering light for exactly five seconds, but the manual only offers the cryptic advice to “listen to the rhythm of the stars.” Another involves complex color-mixing with movable prisms to activate a phase shifter. Damocles Interactive’s designers were apparently part laser physicist, part sadist.

We weren’t just making a game about hint lines. We were making the games that would’ve required hint lines to exist in the first place.

We came up with seven games for the fictional Damocles SWORD console, each designed to be authentically obtuse in different ways. Gorf’s Great Escape was joined by Chronicles of Confuzzlement, a fantasy RPG featuring invisible text that only appears under specific lighting conditions and moral choice consequences that affect everything.

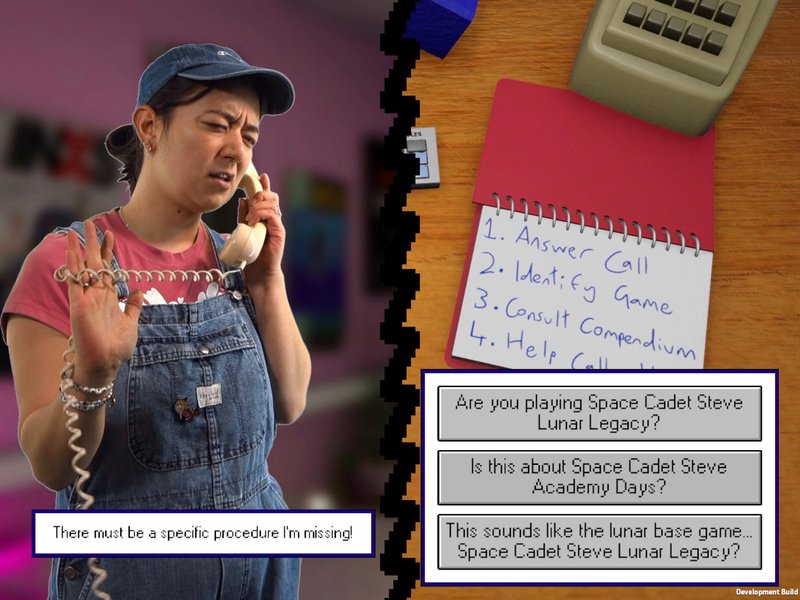

Space Cadet Steve: Lunar Legacy is a point-and-click adventure where hapless cadet Steve must escape a lunar base using illogical puzzle solutions and obscure item combinations.

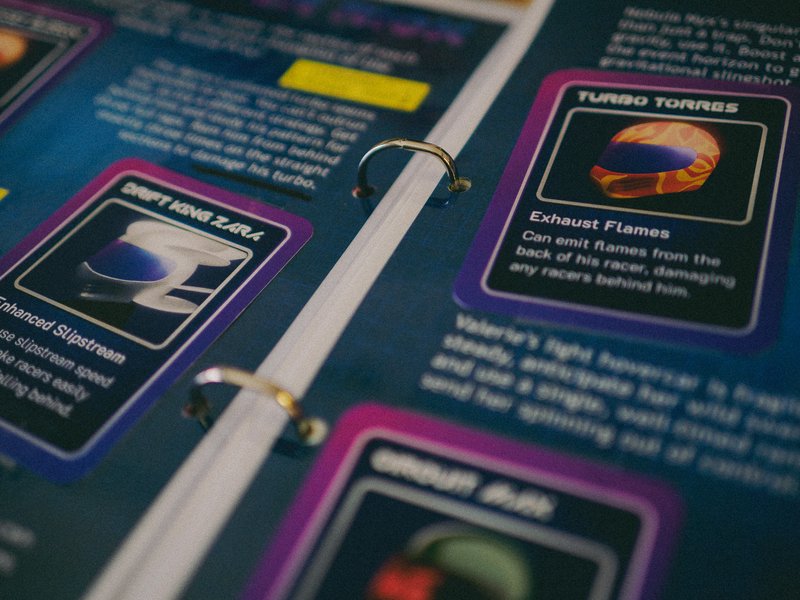

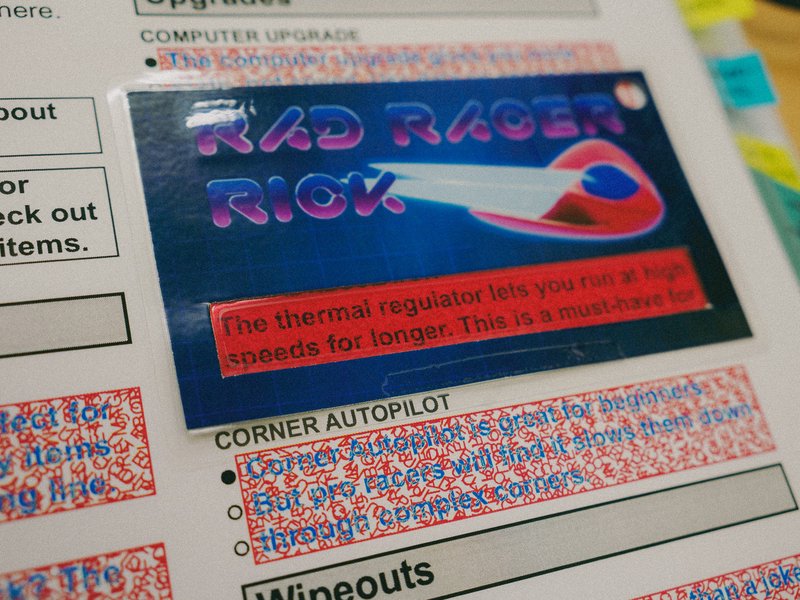

Rad Racer Rick is a revolutionary polygon-based racing game with impossible track geometries and hidden shortcuts never documented in official guides.

Fogg is an atmospheric puzzle adventure set in an abandoned research facility shrouded in perpetual mist, where all critical information is scattered across dozens of journal entries that must be cross-referenced.

Terryble Knight is a comedic medieval platformer that combines precision jumping with adventure puzzles, maintaining Damocles Interactive’s reputation for uncompromising difficulty despite its cartoon styling.

And Cyber Critter Caretaker is a digital pet simulation with evolution mechanics based on algorithmic triggers and real-time care scheduling that continues even when the console is powered off.

Consulting real Sega tip line workers

We didn’t just make this up. Through game journalist Meghann O’Neill, we connected with Brian Costelloe and Tim Gadler, who actually worked Sega’s Australian tip line from 1992 to 1995. Their stories helped take our concept from nostalgia pastiche into something grounded.

Brian started calling Sega’s hotline himself as a teenager, not for hints, but for news about upcoming games. He was making a fanzine called the Sega Times on a dot matrix printer, selling copies to neighbourhood kids and sending them to Sega for feedback. Eventually marketing would transfer him directly to the marketing manager, who’d spend an hour talking games with an enthusiastic kid. When a new manager took over the hotline, Brian got hired almost immediately.

The setup was beautifully makeshift. A small office, green-screen terminals running a basic text-heavy system where you’d pull up game cards. No way to print anything out. Documentation mostly came from Sega of America, sometimes beta ROMs from Japan, but rarely the actual material needed to support the games. Brian made his own folder, covered in magazine clippings and Sonic cutouts, filled with handwritten notes. He still has it. It’s one of the few physical proofs he worked there.

Different counselors became experts on specific games. If you called about Golden Axe Warrior, they’d wait until the person who’d actually finished and mapped it was available, then transfer you. One operator specialised in Might and Magic. Another knew Phantasy Star inside out. You’d share what you learned, constantly updating those game cards with new information.

During school hours, when kids were in class, the “bored housewives” would call. They were into RPGs, especially Phantasy Star. This became our Midday Mum character, a former geological surveyor who plays games during the day, shares unsolicited life tips, and absolutely refuses to accept that racing games aren’t RPGs.

Brian described super fans calling with questions from Japanese magazines most people in Australia would never see. Kids trying to scam their way past the Sega Club membership requirement to get cheats. Bogans ringing up about Shinobi being “bloody hard.” One mother-and-son team who called for every single step of Phantasy Star, from beginning to end, the mum coaching in the background. They finished the game, bought a Mega Drive for the sequel, then never called again because Phantasy Star II came with a hint guide.

After hours, past 6pm closing time, they’d still see calls coming in. For entertainment, they’d manually patch two confused callers together, put themselves on mute, and just listen. One kid ended up helping another through Alex Kidd in Miracle World while the operators sat there going “this is awesome.”

They pranked Nintendo’s hotline. Called asking release dates, stupid questions. Eventually told them “you guys know it’s us at the Sega Hotline, right?” Nintendo stayed stiff and professional. Wouldn’t engage.

Having actual research meant the pitch wasn’t speculative. We could describe specific caller archetypes, specific documentation quirks, specific conversation rhythms because we’d talked to people who lived this.

Mars made four of these by hand

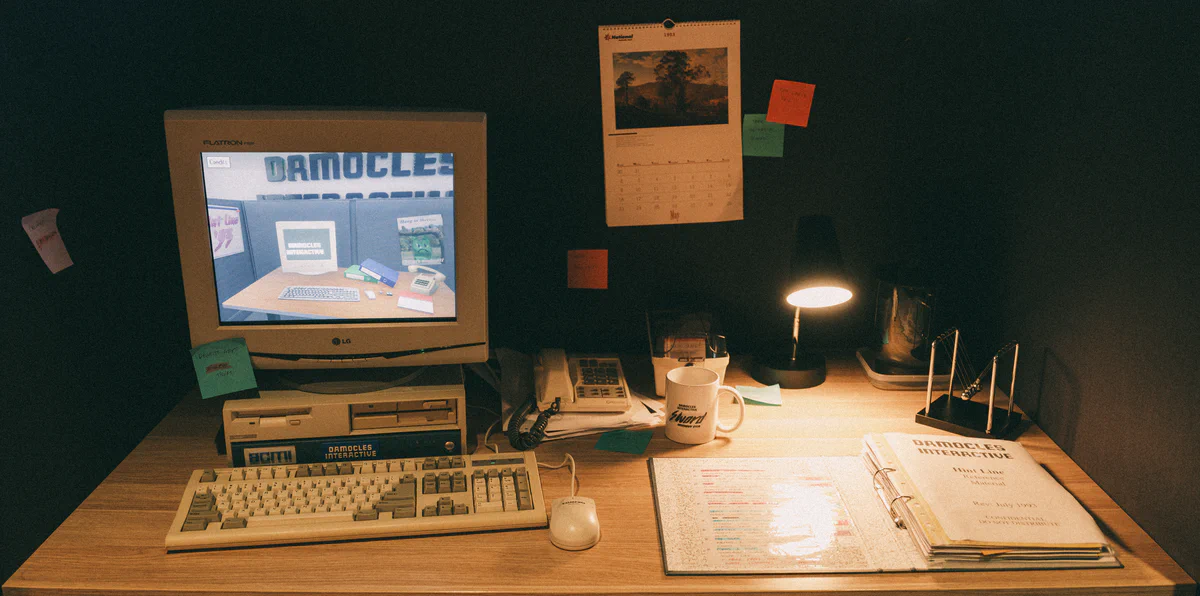

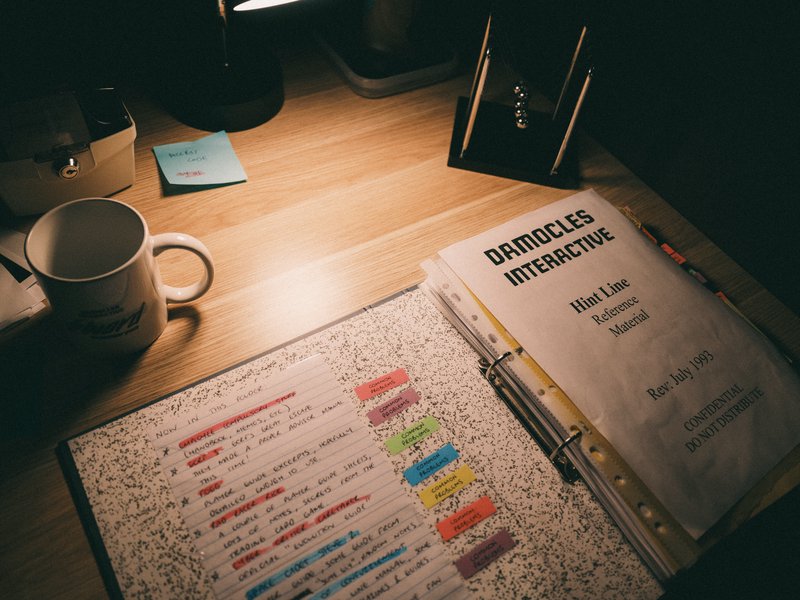

Mars Buttfield-Addison designed and assembled The Compendium, and it became the most ambitious part of the commission. Not just one binder. Four complete copies, each needing to feel genuinely accumulated rather than artificially aged. The Compendium had to be massive, and feel hectic. But also be navigable to actually solve the problems callers had.

Here’s what goes into making a convincing artifact from 1993:

Mars designed decoder wheels in Sketch, printed them on cardstock, cut the circles, and attached them with brass fasteners. She cut red cellophane for anaglyph decoders, the kind of cheap 3D glasses trick that Damocles Interactive would absolutely have used in their instruction manuals. She carefully trimmed the cellophane to fit over specific code tables, glue it to cardstock frames, and did many, many test prints to make sure the secret text was readable.

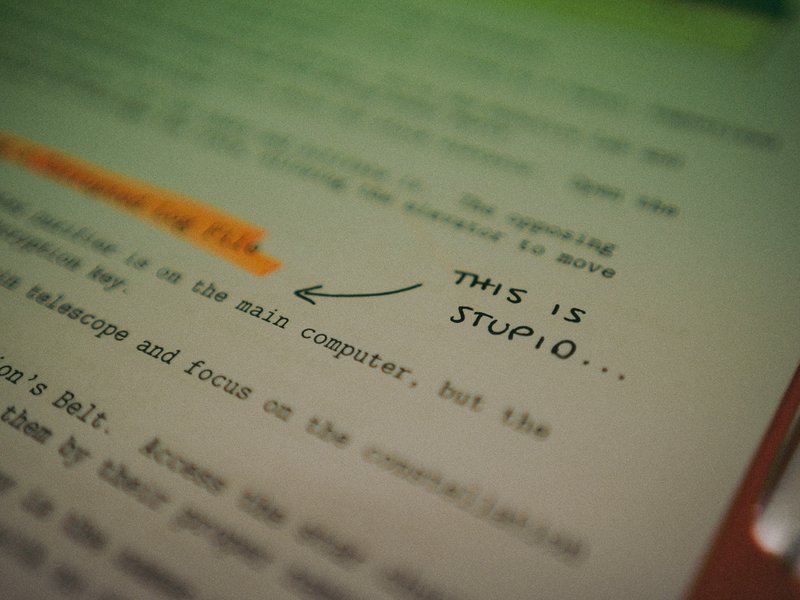

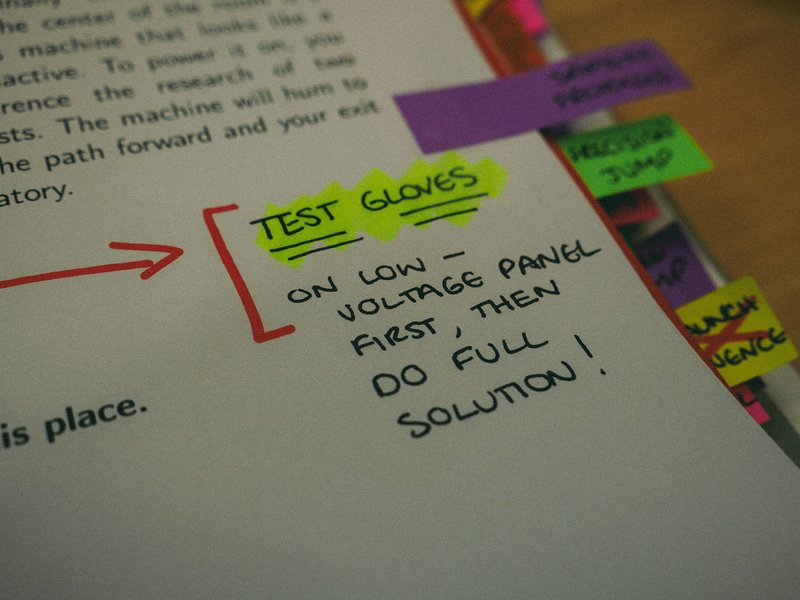

We all write sticky note annotations in different handwriting styles (because multiple counselors would have added their own shortcuts and corrections), and placed them strategically throughout all four binders, trying to remember which pages got which notes. We wrote fan letters from kids, adults, and parents, and created fake pizza menus for the wrong number callers that would ring up and ask for certain pizzas. We wrote corporate memos, fake Usenet posts, game guides, manuals and more.

The binder includes official manual pages with printing errors, photocopied magazine clippings (some photocopied multiple times to get that degraded quality), sticky notes with shortcuts that may or may not work, hand-drawn maps that correct the official versions because someone actually played the game and found out the manual was lying. Internal corporate memos about known bugs. Complaint letters from frustrated customers. The kind of organisational system that only makes sense to whoever created it.

Every crossed-out strategy, every mark, every contradictory piece of advice needed to appear in the right place across four identical binders. You can’t just age one and photocopy it. Physical artifacts don’t work that way. The sticky notes need to be actually stuck. The decoder wheels need to actually spin. The cellophane needs to actually filter the text underneath.

Mars spent weeks at the office conference table with cutting mats, glue sticks, printed pages, brass fasteners, and increasingly elaborate systems to track which binder had which version of which page. The Compendium became an exercise in deliberate, reproducible chaos.

This was the riskiest part of the pitch. Physical artifacts are expensive, they’re fragile in museum contexts, they can’t be easily replicated if something goes wrong. Making four copies meant quadruple the work, but ACMI needed backups and we needed test versions. But the physical elements are also what makes the experience work. Digital-only would have been a game about hint lines. Physical plus digital became playable infrastructure. Of course The Compendium has still partially fallen apart in deployment at the musuem, which was always kind of the point.

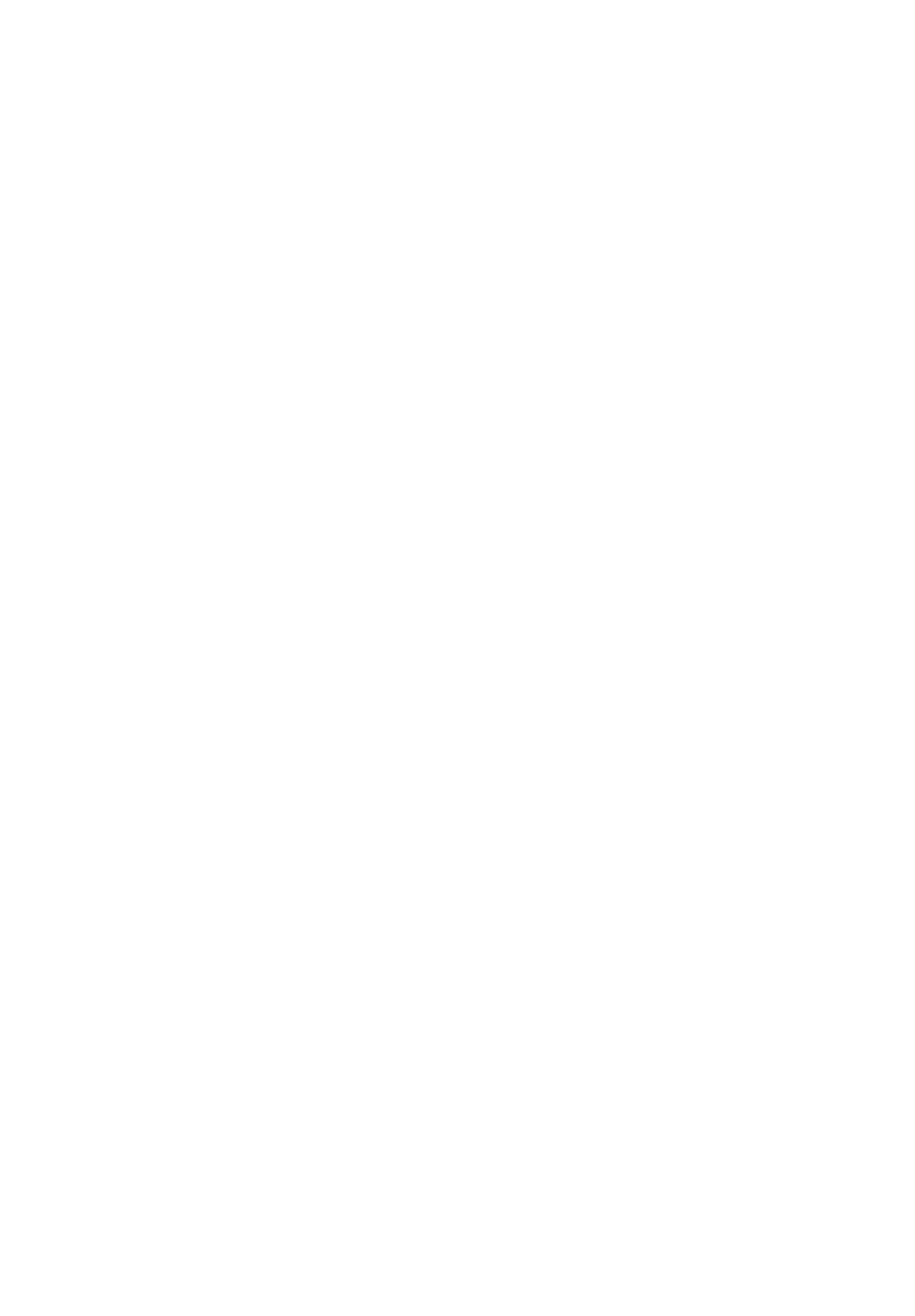

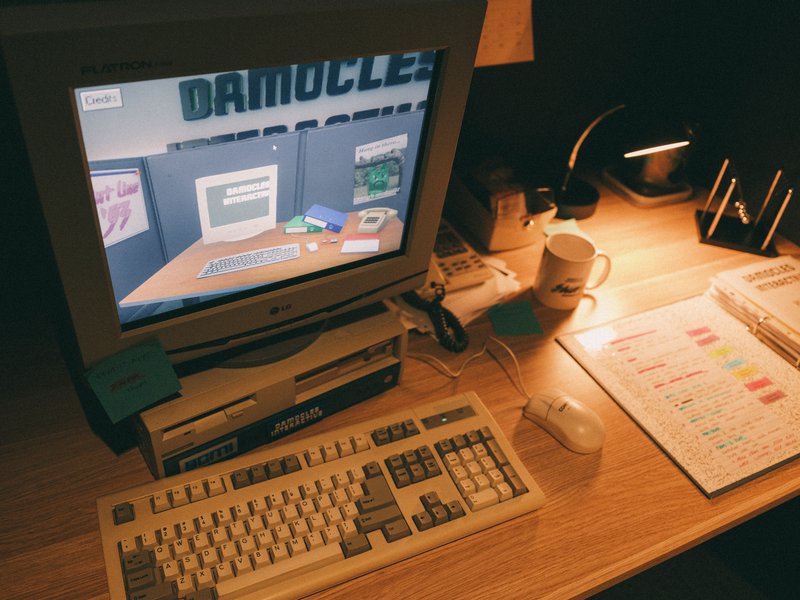

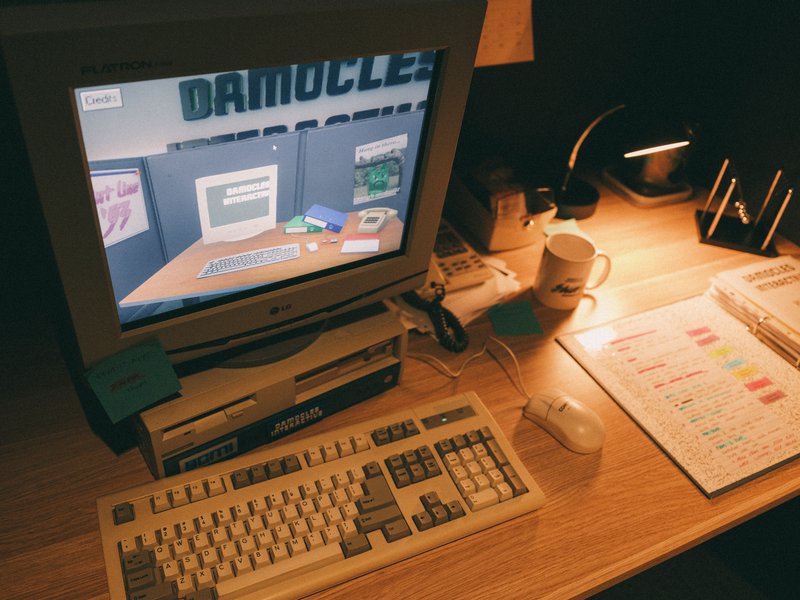

ACMI committed to building the physical installation to match. A a complete 1990s office environment with a vintage cubicle setup was created, with modern hardware hidden inside a beige desktop computer, CRT monitor, the kind of office detritus that made the era charmingly analog. They 3D-printed custom computer case panels branded with ACMI and Damocles Interactive logos, added a Newton’s cradle desk toy and a strategically placed dead plant.

Perfect corporate wasteland aesthetic.

Flipping through the physical Compendium

Writing the callers

The characters needed to feel like real people, not NPC quest givers. Paris wrote most of the archetypes: the paranoid Conspiracy Theorist who grows paranoid when you don’t immediately grasp their conspiracy theories, the smugly condescending Know-It-All who grows frustrated when you don’t immediately know what they want, the breathless Hyper Kid who jumps to conclusions, the methodical Confused Parent determined not to waste their time, and the patient Stressed Completionist who just wants 100% completion without losing their mind.

Meghann created Midday Mum, whose conversations about toxic gas inevitably spiral into microwave chicken safety and geological survey anecdotes, and Tim Nugent wrote the mistaken callers, people looking for pizza delivery or toy store promotions who somehow ended up connected to the Damocles hint line.

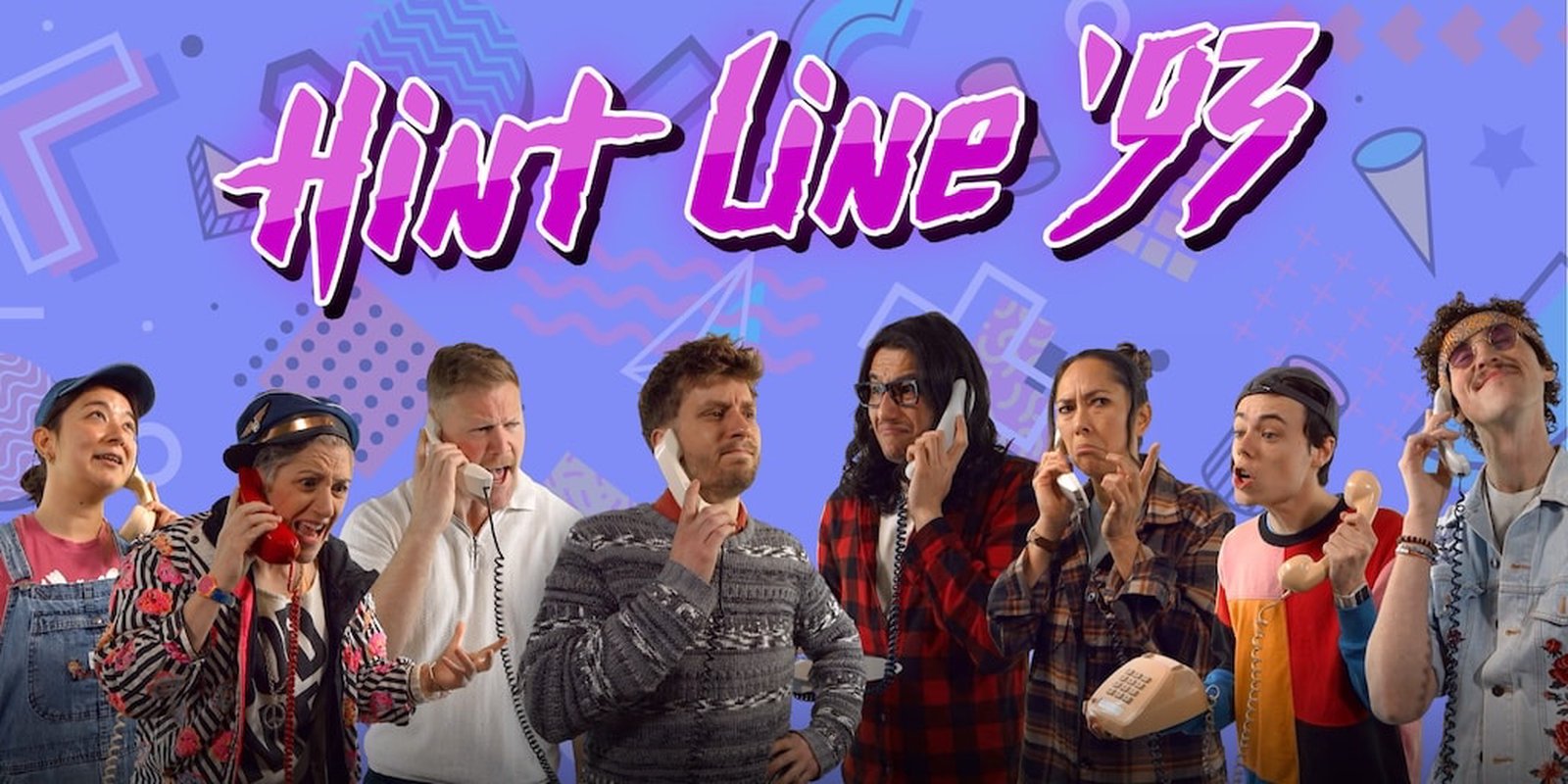

We needed to capture the full emotional range of 1990s gaming frustration through static images alone. We gathered Tasmanian performers in our office studio. Jon Manning directed actors through poses like “shouting at phone,” “smug satisfaction,” and “existential gaming despair,” while Oliver Potter helped with casting and performed himself.

The cast (Oliver Potter, PJ Madam, Mick Davies, emi doi, Scott Lleonart, Bryce Tollard-Williams, Emesha Rudolf, and Harris Sari) each brought their own interpretation of gaming-era emotional states. These aren’t voice recordings. They’re carefully choreographed still images, multiple poses per character that shift based on emotional state as conversations progress. The resulting portraits capture perfect 1990s energy through pure visual storytelling.

The dialogue system uses Yarn Spinner. Each caller brings distinct personality quirks through speech patterns and tangential obsessions. The Know-It-All calls with maximum smugness, then grows frustrated when you don’t immediately understand. The Hyper Kid fires off rapid, breathless questions about temporal locks and impossible jumps. The Confused Parent methodically explains problems with careful precision, someone who does not want to waste a single cent of their call costs.

Conversations derail spectacularly. Ask Midday Mum about toxic gas and she’ll pivot to stories about her life, her profession, and her mysterious number of children (how many does she actually have?), all while insisting you’re wrong about what genre of game she’s playing.

You read text dialogue from callers, then choose from multiple response options after consulting the physical Compendium on the desk. Character portraits shift between emotional poses based on how things progress. A caller starts confused, becomes frustrated if you give unclear advice, shows relief when you finally provide the right hint. This creates the actual rhythm of 1990s hint line work, where success depended on interpreting both the caller’s problem and your available documentation.

Photographing Tasmania’s finest

We decided early on that we’d use photos of real people for our characters. We didn’t have time or budget to get lots of illustration; we could have used 3D assets but it didn’t feel right, and while full-motion video (FMV) is a bit too ambitious, still images with a lot of different poses for emotions feld like it hit the vibe. Shooting the character portraits meant capturing every emotional beat a hint line conversation could hit. Tasmania’s got incredible performing talent and we got lucky.

Oliver Potter cast the project and directed the shoots in our office with a green screen setup. Each actor needed multiple poses. Not just “on phone” but “confused on phone,” “frustrated on phone,” “desperately confused on phone,” “so confused I might cry.” The full range of 1990s gaming emotions.

The results were perfect. The photos are what actual hint line desperation looks like.

Every actor brought something specific. The wild outfits, the genuine confusion, the rising panic. These photos work because everyone understood the assignment: phone-based gaming help and desperation circa 1993.

Tasmania’s performing community is small but incredibly skilled. Getting this caliber of talent in Hobart for a weird microgame about a fictional hint line from 1993 was one of the best parts of the project.

Two months to build it

We built this in two months. The development team was Jon Manning, Tim Nugent, Mars Buttfield-Addison, Paris Buttfield-Addison, and Meghann O’Neill.

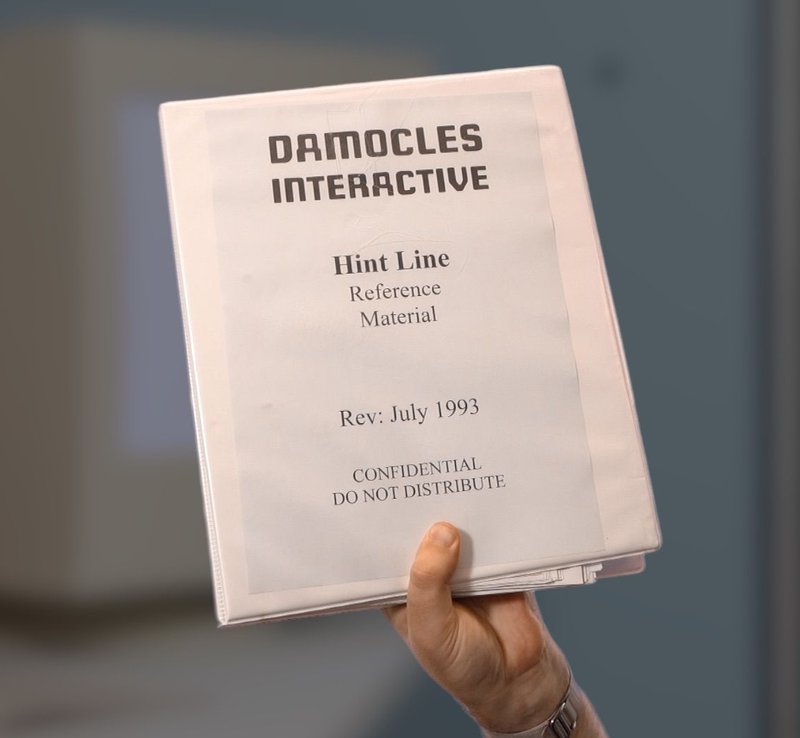

Jon built the game itself in Unity and the in-game images and key art, and designed the Damocles SWORD, catrtridges, and some 3D key art for the games. Tim made the visual novel engine using our upcoming Visual Novel Kit for Yarn Spinner, which became the perfect testbed for a tool we’ll later release publicly.

Paris did most of the pixel art for fictional games, plus their logos, cartridge stickers, fake Usenet post templates, and the like, basically all of of the writing for physical and digital. Meghann wrote the Midday Mum character in-game, and research.

And Mars, who had the hardest job, designed and assembled hundreds of pages of documentation, did all The Compendium art (maps for games, level layouts, page layouts, internal memos, faxes, bug testing reports, and more), assembled The Compendium, and contributed guidance on everything from in-game UX to story. We also found and used a few bits of CC0-licensed art, to fill in the gaps.

The tight timeline forced decisive creative choices and heavy reliance on research. Commission-based work forces you to make things that are actually achievable. No feature creep, no endless refinement. Deliver something real within the constraints. Building with our own unreleased tools meant we could rapidly prototype and iterate, but it also meant debugging in production. Every feature we needed for Hint Line ‘93 became a feature the Visual Novel Kit needed to support.

What made the pitch work, we think, was that we understood the museum context. ACMI wasn’t looking for a commercial game. They wanted experiences that worked as playable exhibits, things that make sense to encounter in a gallery alongside historical artifacts and video installations. ACMI wanted something engaging, and we thought the way to do that was something slightly weird, hectic, silly, and also quite hard.

Hint Line ‘93 functions as both game and historical document, something visitors can play and something that tells a story about disappeared infrastructure.

What we actually made

The final piece is both nostalgia tourism and a game. Hint Line ‘93 is a playable museum exhibit about a disappeared form of human connection. In 1993, getting help with games required talking to another human, someone who might be an expert, might be reading from the same manual you have, or might just be good at confident-sounding guesses.

The hint line represented a moment when gaming was simultaneously more isolated (no online communities) and more social (actual human voices providing help). The Compendium becomes a metaphor for how any complex knowledge system actually functions: layers of official information, unofficial corrections, accumulated wisdom from people who’ve done the work.

Playing Hint Line ‘93 means remembering or experiencing the particular kind of problem-solving that defined early gaming culture. Not instant gratification of looking up solutions online, but slower, more collaborative process of interpreting clues, sharing strategies, building understanding through conversation. Before gaming became fully documented, wikified, speedrun-optimised, it was weird, experimental, mysterious.

The museum context adds meaning. Visitors aren’t just playing a game, they’re handling artifacts of disappeared culture. The Compendium exists as both game component and historical document, something that could theoretically be preserved and studied by future gaming archaeologists trying to understand how people navigated digital entertainment before the internet made everything instantly accessible.

In an era of seamless digital experiences, there’s something satisfying about the deliberate friction of flipping through physical pages while managing digital problems. Technology doesn’t always improve by becoming more efficient. Sometimes the best solutions embrace the beautiful messiness of how humans actually work together to solve problems.

Why the pitch worked

Looking back, we think ACMI said yes because we pitched infrastructure, not nostalgia. If you’re old enough, you probably remember that hint lines existed. We wanted people to experience what it was like to be part of that system.

We had research. Talking to Brian and Tim Gadler meant we could describe specific details, not vague period aesthetics.

We understood the medium. Museum installations aren’t commercial games. They’re playable artifacts that work in gallery contexts.

We committed to physical elements. The Compendium wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was the core of the experience, and we were willing to do the work to make it real.

Next time you tab over to a wiki page or watch a YouTube guide, spare a thought for hint line counselors of the early 1990s, armed with incomplete documentation, good intentions, and hope that the person on the other end was asking about a game they’d actually played. They were unsung heroes of gaming’s most chaotic era, and now, for a few minutes at least, you can experience their particular brand of helpful desperation firsthand.

Where to experience it

The game is playable now at ACMI in Melbourne as part of the Game Worlds exhibition. If you’re in Australia, go sit at a 1990s desk and flip through The Compendium.

Important note: Online is not the intended experience. Flipping through the physical artifact is half the fun. But if you can’t make it to Melbourne:

- See it in ACMI’s collection

- Play it online

- Browse the online Compendium

Development Team

Jon Manning, Tim Nugent, Mars Buttfield-Addison, Paris Buttfield-Addison, Meghann O'Neill

Cast

Oliver Potter, PJ Madam, Mick Davies, emi doi, Scott Lleonart, Bryce Tollard-Williams, Emesha Rudolf, Harris Sari

Special Thanks

Brian Costelloe and Tim Gadler, genuine hint line operators in 1993

Asset Credits

In-Game Assets

Phone Ringing Sound by SoundReality (Pixabay Content License) • TextureChannelPacker by Lasriel (MIT license) • UniTask by Cysharp (MIT license) • Various Textures by ambientCG (CC0 - creativecommons.org/public-domain/cc0/) • Various Textures by PolyHaven (CC0)

Compendium and Marketing Assets

1-Bit Pixel Icons by Nikoichu (CC0) • Abstract Memphis Shapes by Vector Tradition (purchased - Creative Market Content License) • Basic Spells and Buffs Icons by Atelier Pixerelia (terms as at pixerelia.itch.io/vas-basic-spells-and-buffs) • Castle Building Vector by GDL (Pixabay Content License) • Open Peeps by Pablo Stanley (CC0) • Pixel-Art Space Background by Virusystem (CC0) • Pixel Office Asset Pack by 2dPig (CC0) • Pizza Cartoon Characters by Sketch Master (purchased - Shutterstock Standard Image License) • Space Station Ada by Jestan (CC BY 4.0 - creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) • Space Station Pack by lukyaforge (purchased - terms as at lukyaforge.itch.io/test) • “The Base Mesh” Model Library (CC0) • Twemoji icons (CC BY 4.0)

Fonts

Alagard by Hewett Tsoi (“Give credit if used. That’s it.”) • Benecarlo by FontSite (purchased - Fontsprint Worry-Free Font License) • Computer Modern by Donald Knuth (SIL Open Font License) • Lazenby Computer by Disaster Fonts (CC BY-SA 4.0, creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/) • Long Haired Freaky People (purchased - Chequered Ink “All Fonts” Commercial Font License) • Misery Gymnast (purchased - Chequered Ink “All Fonts” Commercial Font License) • Wheaton by Raymond Larabie (FFC - 1001Fonts Free For Commercial Use License) • Yurine Overflow by GemFonts (FFC - 1001Fonts Free For Commercial Use License)

Everything else was made by hand, by us, with love. No GenAI was involved in any part of this project.